Lunar Resource Precedents and the Definition of “Collected”

Why it matters

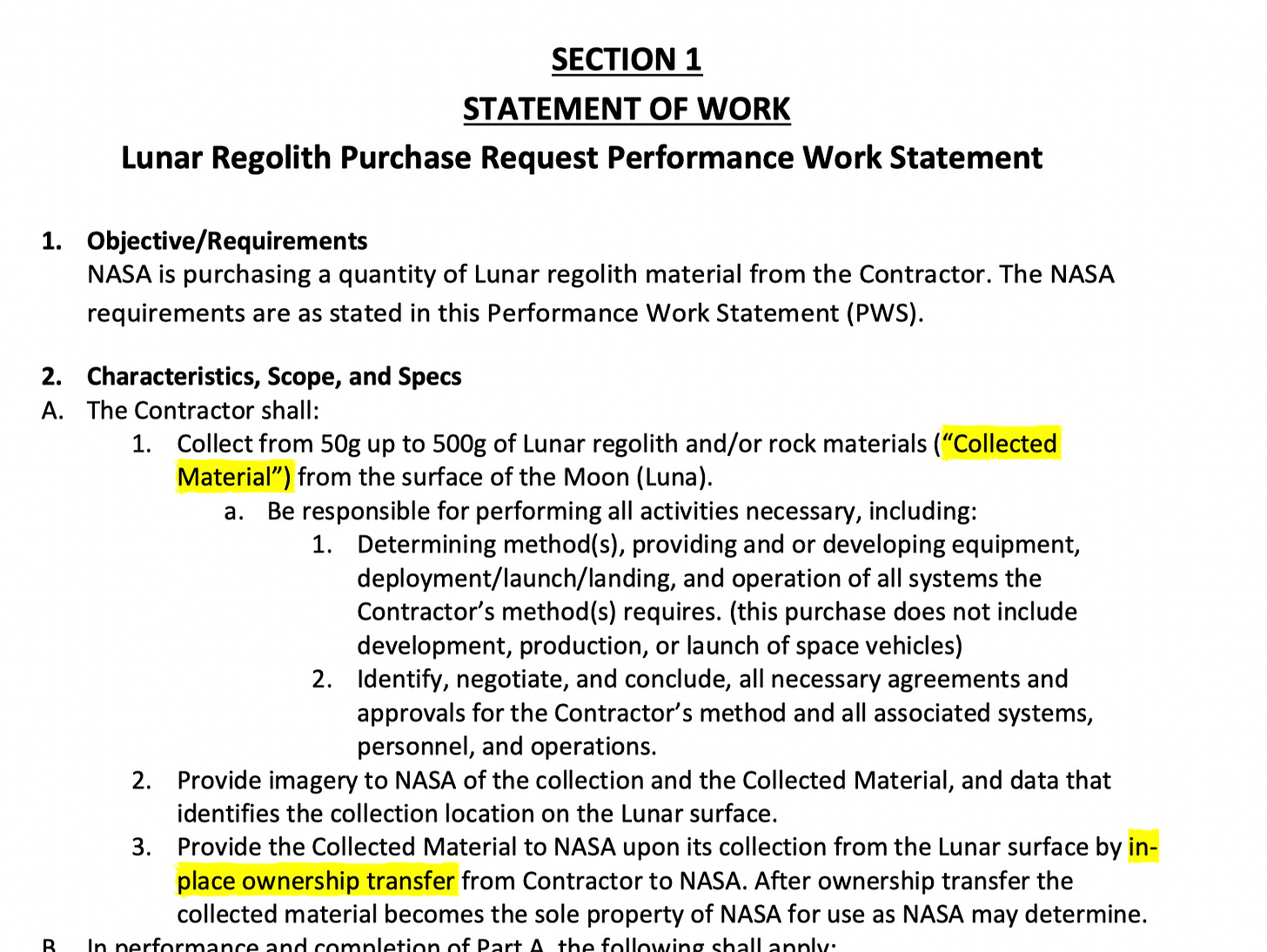

NASA is planning to pay commercial companies a nominal amount for “collected” regolith at the lunar surface. They aim to demonstrate two precedents:

That it is permissible to appropriate non-land resources on the Moon

That it is permissible to transact those resources commercially.

These are new in the following ways: although resources on the Moon have been collected numerous times, and objects on the Moon have been sold before, the combination of natural resources being collected AND privately transacted upon is new.

With the relatively small volume (50-500g) and no plans for use or retrieval, some may see the precedent as gimmicky. But gimmicky or not, it is likely to be referenced and built upon. The fact that the amounts are so small, or that there are no plans for retrieval, makes it easy to dismiss— but that also makes it easy to take actions with unclear or unintended consequences. So it’s worth thinking about, and articulating, under what conditions this kind of transacting is compliant with the Outer Space Treaty (OST), and how it could advance a coherent and productive approach to resource management on the Moon (or other celestial bodies).

NASA’s approach to this contract is to keep things as minimal as possible. The term ‘ownership’ is not explicitly defined. The Request for Quotation (RFQ) text involves a tacit assumption about the right to transact these resources, which is undergirded in the US by the 2015 Space Act. A government agency paying for it reinforces the idea yet again. But the right to transact resources in general and the conditions under which it is legitimate are two different questions. NASA’s approach seems to implicitly put responsibility on the seller to assert they have a right to sell these resources in the first place, freeing NASA (among others) from having to articulate the finer points of transaction legitimacy.

Although the 2015 law is a starting point, it doesn’t answer all the questions. In particular, the threshold of when something becomes ownable is a critical issue we need to engage with if we want to preserve the OST while developing a viable international approach to resource utilization. I am not a lawyer, and am not particularly knowledgeable about these aspects of environmental and property law, including the definition of natural resource extraction. I imagine there are terrestrial precedents here we can draw on to create clear delineations. But as far as I can tell, no one is consulting those experts in order to ground these precedents for the Moon.

Assuming we start from a position that private ownership of extracted resources (as opposed to land) is, in general, permissible under the OST (which is still a contested if increasingly majoritarian position): we need a well grounded rationale to legitimate that claim, including when something exits the domain of “national appropriation” (Article II)—equated in space law circles to territorial appropriation— and enters the domain of being “appropriable.”.

The burden of proof is truly on those who want to advance this interpretation of the law; otherwise, the interpretation may be denied or resisted by the international community.

Grey Areas

The principle distinction being made to justify transactions on space resources is that they be differentiated from the land itself. This is most commonly referred to as “extracted” resources. In NASA’s RFQ, there is another word: “collected.”

Because NASA is only paying a nominal amount for these resources (between $1 and $15k), the mechanisms for collection will naturally involve as little spacecraft modification as possible, emphasizing passive collection without mechanical components, data or power needs. This has generated some really creative thinking, but also exacerbates some of the questions around legitimacy.

Commercial actors I have spoken with genuinely want to advance and mature the legal framework around space resources, which is a big part of why they would even consider participating in a contract valued so low. They are not trying to pull the wool over anyone’s eyes, they are participating in an experiment with the hopes of creating greater clarity in support of ambitious future missions.

Some mechanisms being discussed for regolith collection include:

Dust displaced by the approaching spacecraft, or by the physical settling of the landing gear, falling into pre-defined receptacles on a lander.

Regolith compressed between the tread of rover wheels.

Active or passive creation of a “pile” such as one might see at a construction site.

Regolith gathered in a passive scoop jutting out from a lander leg, or inside the footpad of the lander leg.

These raise some fascinating—and important—questions. What defines the collected resource? When does it go from something we would call “land” to being an object we can appropriate and sell? What if the lofted dust landed on solar panels instead of in these cups? Could we still make the same claims to ownership? And what rights and obligations does that claim entail? If the dust gets blown off by another spacecraft, can I claim damages or harm?

Can resources be considered 'collected' but not movable, or without being contained? If a collected resource sits on an inactive spacecraft occupying a site of interest to future missions, does this go against the freedom of access principle (Article I)?

Other definitions are grey too: we don’t have a shared definition of ownership under the OST. Ownership is often presumed to mean the right of exclusion, or the right to alienate (sell or lease) the property in question. But it can mean all manner of things in the broader landscape of property and resource management regimes: resources can be appropriated and managed by governments or by groups of stakeholders, not just individuals, and often comes with responsibilities as well as rights.

As buyers and sellers, we have to ask when, or whether, we want to reinforce these claims. I am worried that if we’re imprecise about the definition of "collection," it will set an undesirable precedent for what can be considered property, and what can or cannot be commodified on the lunar surface. Strong definitions will strengthen the regime we have, while offering an opportunity to advance a clear model of legitimate transacting. Without good definitions, we will see disputes, confusion, and possible erosion of the non-appropriation principle itself.

What to do about it

Here are some actions we can take:

Engage natural resource lawyers to understand how these questions are handled in terrestrial contexts.

Introduce qualifiers or requirements for 'collection,' for example (these are just ideas):

Clarify intent: for example, “active and willfully” collected.

The requirement for matter to be moved “out of place.”

The ability to characterize the resource accurately or sufficiently; e.g. to have a known weight or volume.

The idea of persistent integrity (the “it” can be defined and the "it" will stay the same)

The collected resource is subsequently movable.

Civil society dialogs and government policy makers can take on the question and advance clear definitions of collection, appropriation and ownership, including associated rights and responsibilities.

Member states and observers should raise the question of the definition of “collection” at UN COPUOS and seek a definition of collection and extraction consented by all parties.

Sue the US government. (Ok, I’m not really serious here, but in the spirit of completeness: the OST is law in the United States. If enough Americans felt that the government was not upholding its obligations under that law, perhaps a lawsuit could be brought) (*note that I subsequently had a conversation with a colleague about this and unsurprisingly it is complicated).

Offer additional ways that commercial actors can demonstrate positive, credible mechanisms for collection on early missions.